Weeding Out Corporate Psychopaths

Given the state of the global economy, it might not surprise you to learn that psychopaths may be controlling the world. Not violent criminals, but corporate psychopaths who nonetheless have a genetically inherited biochemical condition that prevents them from feeling normal human empathy.

Scientific research is revealing that 21st century financial institutions with a high rate of turnover and expanding global power have become highly attractive to psychopathic individuals to enrich themselves at the expense of others, and the companies they work for.

A peer-reviewed theoretical paper titled “The Corporate Psychopaths Theory of the Global Financial Crisis” details how highly placed psychopaths in the banking sector may have nearly brought down the world economy through their own inherent inability to care about the consequences of their actions.

The author of this paper, Clive Boddy, previously of Nottingham Trent University, believes this theory would go a long way to explain how senior managers acted in ways that were disastrous for the institutions they worked for, the investors they represented and the global economy at large.

If true, this also means the astronomically expensive public bailouts will not solve the problem since many of the morally impaired individuals who caused this mess likely remain in positions of power. Worse, they may be the same people advising governments on how to resolve this crisis.

To tackle this problem, we must instead examine this rare and curious condition, and why recent corporate history may have elevated precisely the wrong type of people to positions of great power and public trust.

Unfeeling, but not insane

Psychopathy should not be confused with insanity. It is best described by Robert Hare, global expert and psychologist, as “emotional deafness” — a biochemical inability to experience normal feelings of empathy for others.

This shark-like fixation on self-interest means that psychopaths often feel a clear detachment from other people, viewing them more as sheep to be preyed upon than fellow humans to relate to. For instance, psychopaths in prison often use group therapy sessions not as a healing process, but as an opportunity to learn how to simulate normal human emotions.

Studies on twins have revealed that psychopathy shows a strong genetic signature and there remains no effective treatment. Recent research has linked the condition to physical abnormalities in the amygdala region of the brain.

Only a small subset of psychopaths become the violent criminals so often fictionalized in film. Most simply seek to blend in and conceal their difference in order to more effectively manipulate others. This frightening condition has existed throughout human history, though likely in a marginal and socially parasitic way.

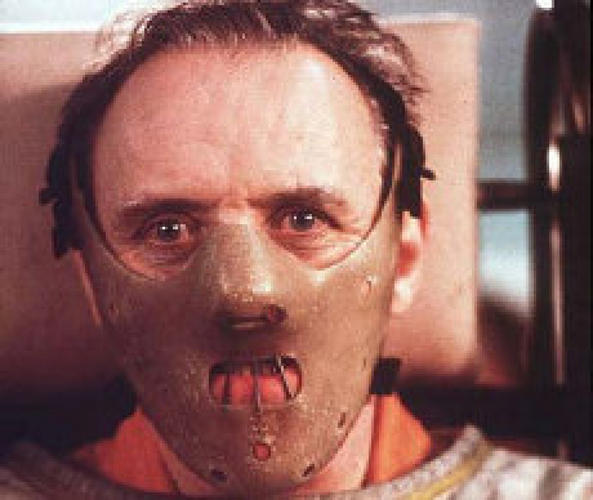

While psychopaths are often portrayed by Hollywood as brilliantly clever, a hypothetical race of Hannibal Lecters would likely perish since they lack the ability to trust each other. Put another way, the human race — a relatively weak, slow, hairless tropical primate — has succeeded so spectacularly in every ecosystem on the planet not because we are so bad, but because we are so good.

Most dangerous 1 per cent

The human ability to build social capital means that people can cooperate and trust each other. We can reliably predict the behavior of others even if we have never met them. Social capital is the glue that holds together our communities, complex societies, large institutions and the economy. The one and only superpower possessed by psychopaths is their ruthless ability to spend the social capital created by others.

Scientists believe about 1 per cent of the general population is psychopathic, meaning there are more than three million moral monsters among normal United States citizens. There is emerging evidence that this frequency increases within the upper management of modern corporations. This is not surprising since personal ruthlessness and fixation on personal power have become seen as strong assets to large publicly traded corporations (which some authors believe have also become psychopathic).

However, appearance and performance are two different things. While psychopaths are often outwardly charming and excellent self-promoters, they are also typically terrible managers, bullying co-workers and creating chaos to conceal their behavior.

When employed in senior levels, their pathology also means they are biochemically incapable of something they are legally required to do: act in good faith on behalf of other people. The banking and corporate sector is built on the ancient principle of fiduciary duty — a legal obligation to act in the best interest of those whose money or property you are entrusted with. Asking a psychopath to do that is like recruiting a pyromaniac to be a firefighter.

The folly of mixing psychopathy and senior corporate management has been borne out by recent history. At the end of the last decade, numerous banking institutions representing hundreds of years of corporate financial stability ceased to exist within a few short months due to the reckless acts of a few individuals — none of whom has ever been charged with a crime.

And therein lies the rub. As ruthless as psychopaths are, their pathology dictates that they will ultimately act to the detriment of the organizations and investors they are paid so well to represent.

Fertile for psychopaths: New corporate culture

If this theory is correct, how did this become such a crisis in recent decades? Boddy suggests that corporations have changed from relatively stable institutions where psychopaths would have a difficult time concealing themselves, to highly fluid organizations where it is much easier for them to disappear within the chaos in their wake.

“(The) whole corporate and employment environment changed from one that would hold the Corporate Psychopath in check to one where they could flourish and advance relatively unopposed,” Boddy writes. “As evidence of this, senior level remuneration and reward started to increase more and more rapidly and beyond all proportion to shop floor incomes and a culture of greed unfettered by conscience developed. Corporate Psychopaths are ideally situated to prey on such an environment and corporate fraud, financial misrepresentation, greed and misbehavior went through the roof, bringing down huge companies and culminating in the Global Financial Crisis that we are now in.”

Boddy is not hopeful that the current round of expensive public bailouts will solve the problem. If psychopaths have in fact installed themselves in the upper reaches of the world’s financial institutions, their genetic deficiency dictates that their greed knows no bounds. They will continue to act in anti-social, remorseless ways, amplified by their enormous corporate influence until the institutions they represent and perhaps the entire global economy collapses. Obviously, more academic research in this area is urgently needed.

Boddy concludes his recent paper with this grim prediction:

“Writing in 2005, this author . . . predicted that the rise of Corporate Psychopaths was a recipe for corporate and societal disaster. This disaster has now happened and is still happening. Across the western world, the symptoms of the financial crisis are now being treated. However, this treatment of the symptoms will have little effect because the root cause is not being addressed. The very same Corporate Psychopaths, who probably caused the crisis by their self-seeking greed and avarice, are now advising governments on how to get out of the crisis. That this involves paying themselves vast bonuses in the midst of financial hardship for many millions of others is symptomatic of the problem. Further, if (this theory is correct) then we are now far from the end of the crisis. Indeed, it is only the end of the beginning. Perhaps more than ever before, the world needs corporate leaders with a conscience . . . Measures exist to identify Corporate Psychopaths. Perhaps it is time to use them.”

Time has come for testing

Boddy’s last statement contains a kernel of hope. If our world has become chaotic due to institutionalized psychopathy, imagine how much better it could be if such dangerously impaired individuals were excluded from positions of power and influence.

Precedence exists for dealing with such situations. Randomized workplace drug testing became the norm in the 1980s. At the time, civil libertarians strongly objected on the basis that it violated personal privacy protections. However, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in 1989 that such testing was constitutional and now about 25 per cent of Fortune 500 companies routinely require their employees to submit to such tests.

Perhaps investors at major financial institutions should require that senior level managers submit to established tests to ensure they are not psychopathic. This is not an issue of civil liberties since the precedent has already been well established regarding drug impairment in the workplace. Likewise, it is not a regulatory issue since private shareholders have every right to demand that executives demonstrate they are not biochemically impaired and therefore unable to carry out their fiduciary duties on behalf of investors. If corporate boards are hiring psychopaths as executive management, they are not carrying out their due diligence and could be held legally liable for their oversight.

Companies should also consider providing employees with specific whistleblower provisions to expose potential psychopaths in the workplace. A 2010 study by Boddy showed that corporate psychopaths caused more than one quarter of all workplace bullying, though they accounted for only one per cent of the workforce.

Besides being traumatic and humiliating to other workers, this bullying is also very expensive. Boddy calculated that bullying by corporate psychopaths cost companies in the U.K. more than £3.5 billion per year in lost productivity and attrition. Extrapolating these results to the United States, these deviant individuals are responsible for more than $35 billion in direct annual losses to U.S. businesses.

Politicians, too?

And what about elected officials? There is no higher standard of trust in our society than standing for public office. Campaigning politicians are expected to submit to almost absurd levels of scrutiny about their private lives, character and personal relationships. Should not candidates begin providing voters proof that they are medically capable of acting in the interests of the public that may elect them?

The Occupy Wall Street protesters demanding an end to the reign of the “1 per cent” may have unwittingly stumbled on the crux of the issue. Science tells us that 99 per cent of humans have normal emotional function. One per cent are psychopaths. We ignore that truth at our peril.

© 2011 Toronto Star